|

Continuing a series of posts on the so-called Tai Chi "energies," let's talk about An Jin, or "Push" energy. And a reminder, the "energies" of Tai Chi are simply refined methods of dealing with force. A "Jin" is a way of dealing with an opponent's force in a refined way that requires a lot of practice.

You don't use brute force. The Taiji energies require skill.

The word "energy" has sparked a lot of woo-woo nonsense that has attracted people to the art who are looking for magic powers and fairy dust instead of martial art.

An Jin -- Push -- isn't really about "pushing" the way we think about pushing. It's about direction, pressure, and timing. It is a downward, forward pressure that is issued in connected weight sinking. It is expressed not with arm force, but with a whole-body connection.

Looking at the first four energies of Taiji: Peng is buoyancy, Lu is redirection, Ji is compression, and An is gravity with intent.

The two-handed push, as in most Taijiquan forms (pictured above from the Yang 24 form), is overemphasized because it's easy to teach, easy to feel, and easy to demonstrate. But just like with Ji Jin (Press), if you think of An Jin as a two-handed push, you are confusing posture with Jin.

If you push someone with one or two hands, even if you use connected, whole-body movement, even if you don't use localized shoulder and arm muscle to push, and even if you sink after the push, you are primarily using Peng Jin.

If you push someone backward with arm strength, leaning and bracing, it looks like An, and students will think, "Oh, I get it. It's being relaxed as you push someone."

Instead of thinking about An Jin as a forceful extention, think of An Jin this way: it is organized sinking.

An is not something you do to the other person; it's what happens when your structure settles and they're in the way.

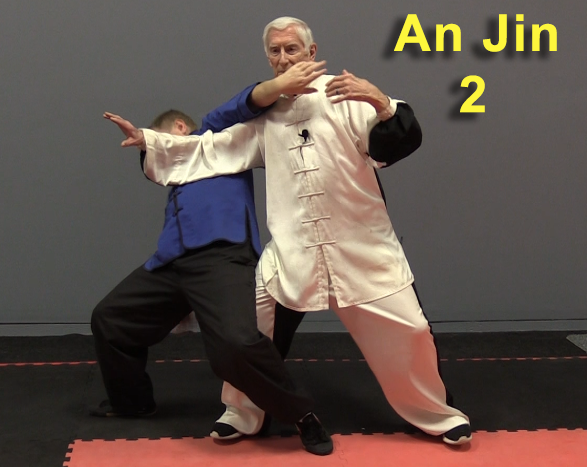

So let's use the example of Walking Obliquely, and the sinking at the end which can be used to take an opponent down because my leg is behind him. Take a look at this photo:

|